From April 1st, 2016, to March 31st, 2017, 48 hemodialysis units took part in the surveillance of vascular access–related bloodstream infections (VARBSIs) in hemodialysis (HD) patients, for a combined total of 57,570 patient-periods (Table 1). Participating units reported 127 VARBSIs in 120 patients. Patient-periods involving a fistula account for 40.7% of patient-periods. The VARBSI incidence rate is 0.06 cases per 100 patient-periods for patients with an arteriovenous (AV) fistula, 0.10 for patients with a synthetic fistula (graft), 0.32 for patients with a tunneled catheter and 1.24 for patients with a non-tunneled catheter. In 2016–2017, incidence rates for tunneled and non-tunneled catheters have significantly decreased compared to rates for 2012-2016 (p < 0.05) while rates for AV fistulas and grafts have remained stable. Since 2015-2016, three HD units joined the surveillance. Data were extracted on May 5th, 2017.

Update : October 5, 2017

Version française

Table 1 – Participation of Hemodialysis Units in the Surveillance of VARBSIs in Hemodialysis Patients, Québec, 2012–2013 to 2016–2017

2012-2013 | 2013-2014 | 2014-2015 | 2015-2016 | 2016-2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Units (N) | 42 | 42 | 45 | 45 | 48 |

| Patients monitored (average number per period) | 3,977 | 3,984 | 4,303 | 4,217 | 4,428 |

| Patient-periods (N) | 51,697 | 51,791 | 55,939 | 54,818 | 57,570 |

| Patient-months (N) | 48,340 | 48,469 | 52,316 | 51,457 | 53,876 |

| Dialysis sessions (N) | 621,516 | 623,172 | 672,639 | 661,588 | 692,697 |

| Catheter-days (N) | 798,816 | 824,834 | 891,802 | 910,884 | 958,343 |

| VARBSIs (cat. 1a, 1b and 1c, N) | 206 | 150 | 154 | 132 | 127 |

| VARBSIs with AV fistulas or grafts (N) | 44 | 25 | 23 | 17 | 14 |

| VARBSIs with tunneled or non-tunneled catheters (N) | 162 | 125 | 131 | 115 | 113 |

| Infected patients (N) | 199 | 142 | 142 | 125 | 120 |

Incidence rates

The 2016-2017 VARBSI incidence rate was 0.22 cases per 100 patient-periods. The incidence rate was 0.06 for patients with an AV fistula, 0.10 for patients with a graft, 0.32 for patients with a tunneled catheter and 1.24 for patients with a non-tunneled catheter (Figure 1). In patients with AV fistulas, the VARBSI incidence rate was higher when the buttonhole technique was used (0.17 per 100 patient-periods versus 0.04, p < 0.05); the incidence rate for patients with tunneled catheters is higher than for patients with an AV fistula without buttonhole (p < 0.05); the incidence rate for patients with non-tunneled catheters is statistically higher than the rate for patients with a permament catheter (p < 0.05).

Therefore, compared to AV fistulas without buttonhole, the incidence rate with a non-tunneled catheter is 32.7 [11.0 ; 97.0] times greater (p < 0.05), with a tunneled catheter, 8.3 [4.1 ; 19.5] times greater (p < 0.05), with a graft 2.6 [0.4 ; 11.6] times greater (p > 0.05) and with an AV fistula with a buttonhole, the incidence rate is 4.5 [1.3 ; 14.7] times greater (p < 0.05). The incidence rate with a non-tunneled catheter is 3.9 [1.7 ; 8.0] times higher than with a tunneled catheter (p < 0.05), this rate itself 5.2 [3.1 ; 9.6] higher than the rate for patients with an AV fistula or a graft (p < 0.05).

Figure 1 – VARBSI Incidence Rate by Type of Vascular Access, Québec, 2016–2017 (Incidence Rate per 100 Patient-periods [95% CI])

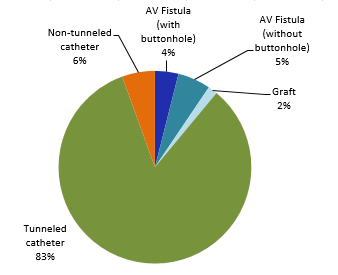

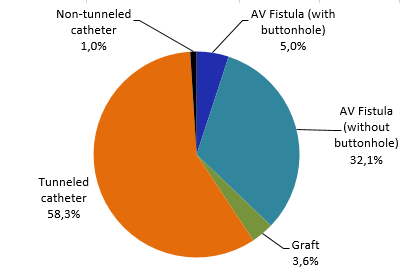

Tunneled catheters are the most commonly used type of vascular access (58%), followed by AV fistulas without the use of the buttonhole technique (32%, Figure 2). The proportion of patients with a fistula or a graft is 41%.

Figure 2 – Breakdown of Patient-Periods by Type of Vascular Access, Québec, 2016–2017 (%)

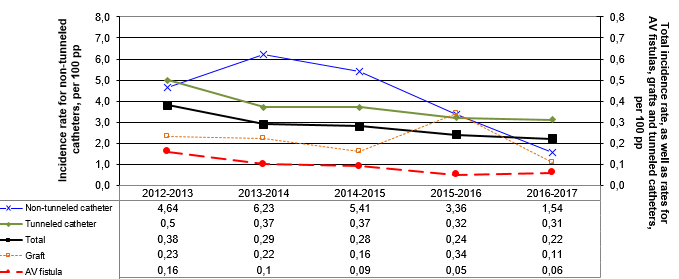

Incidence rates time trends

In 2016–2017, incidence rates for tunneled and non-tunneled catheters have significantly decreased compared to rates for 2012-2016 (p < 0.05, Table 2 and Figure 3) while rates for AV fistulas and grafts have remained stable. A general decreasing trend can be observed in units participating since 2012-2013 (Figure 4).

Figure 3 – Evolution of VARBSI Incidence Rates by Type of Vascular Access in Units That Have Previously Participated (N=45), Québec, 2012–2016 and 2016–2017 (Incidence Rate per 100 Patient-Periods [95% CI])

NB: Incidence rates for AV fistulas, with or without buttonhole, are rates for 2013-2016 and 2016-2017, as information on the use of the buttonhole technique was not collected before 2013-2014.

Table 2 – Evolution of VARBSI Incidence Rates by Type of Vascular Access in Units That Have Previously Participated (N=45), Québec, 2012–2016 and 2016–2017 (Incidence Rate per 100 Patient-Periods and per 1,000 Vascular-Access-Days [95% CI])

| Type of vascular access | Incidence rate /100 patient-periods [95% CI] | Incidence rate /1.000 vascular-access-days. [95% CI] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

2012-2016 | 2016-2017 | 2012-2016 | 2016-2017 | |

| AV fistula or graft | 0.12 [0.10 ; 0.14] | 0.06 [0.04 ; 0.11] | --- | --- |

| AV fistula | 0.11 [0.09 ; 0.13] | 0.06 [0.03 ; 0.10] | --- | --- |

| With buttonhole* | 0.40 [0.31 ; 0.52] | 0.18 [0.08 ; 0.44] | --- | --- |

| Without buttonhole* | 0.04 [0.03 ; 0.06] | 0.04 [0.02 ; 0.08] | --- | --- |

| Graft | 0.23 [0.15 ; 0.35] | 0.10 [0.03 ; 0.41] | --- | --- |

| Tunneled or non-tunneled catheter | 0.44 [0.40 ; 0.48] | 0.33 [0.27 ; 0.40] | 0.16 [0.14 ; 0.17] | 0.12 [0.10 ; 0.14] |

| Tunneled catheter | 0.40 [0.36 ; 0.43] | 0.31 [0.25 ; 0.38] | 0.14 [0.13 ; 0.15] | 0.11 [0.09 ; 0.13] |

| Non-tunneled catheter | 4.85 [3.72 ; 6.31] | 1.52 [0.72 ; 3.19] | 1.72 [1.32 ; 2.25] | 0.55 [0.26 ; 1.15] |

| Total | 0.30 [0.28 ; 0.32] | 0.22 [0.18 ; 0.26] | 0.16 [0.14 ; 0.17] | 0.12 [0.10 ; 0.14] |

* Incidence rates for AV fistulas, with or without buttonhole, are rates for 2013-2016 and 2016-2017, as information on the use of the buttonhole technique was not collected before 2013-2014.

Figure 4 – Evolution of VARBSI Incidence Rates by Type of Vascular Access, for Units Participating Since 2012–2013 (N = 40), Québec, 2012–2013 to 2016–2017 (Incidence Rate per 100 Patient-periods)

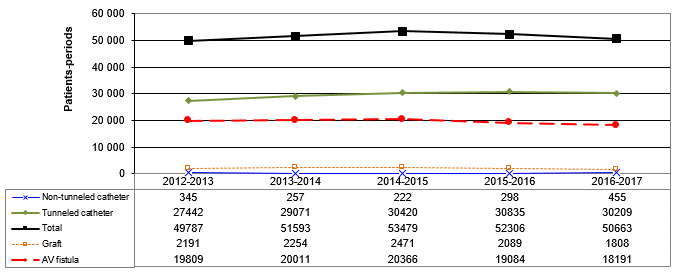

Despite recommendations, the proportion of patients receiving hemodialysis through a catheter, either non-tunneled or tunneled, increased in 2016–2017 compared with 2012–2016 (p < 0.05, Table 3 and Figure 5). In addition, the proportion of patients with a non-tunneled catheter, which is the form of vascular access most likely to lead to a VARBSI, increased significantly (p < 0.05).

Figure 5 – Time Trends in Patient-Periods by Type of Vascular Access, for Units Participating Since 2012–2013 (N = 40), Québec, 2012–2013 to 2016–2017

Table 3 – Breakdown of Patient-Periods by Type of Vascular Access, 2012–2016 and 2016–2017 (%)

| Type of vascular access | 2012-2016 | 2016-2017 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

N | % | N | (% | |

| AV fistula | 82,773 | 38.7 | 20,310 | 37.1 |

| With buttonhole* | - | - | 2,758 | 5 |

| Without buttonhole* | - | - | 17,552 | 32.1 |

| Graft | 9,269 | 4.3 | 1,966 | 3.6 |

| Tunneled catheter | 120,836 | 56.5 | 31,982 | 58.4 |

| Non-tunneled catheter | 1,135 | 0.5 | 461 | 0.8 |

| AV fistula or graft | 92,042 | 43 | 22,276 | 40.7 |

| Tunneled or non-tunneled catheter | 121,971 | 57 | 32,443 | 59.3 |

| Total (N) | 214,013 | 100 | 54,719 | 100 |

Description of cases

Patients who developed a VARBSI are aged between 0 and 99 years, with a median age of 68 years. The vast majority (89%, or 113 cases) of VARBSIs occurred in patients who receive their hemodialysis treatment via catheter, even though they represent only 59% of the patient-periods monitored (Figures 2 and 6). For 42% of the cases that arose in patients receiving their hemodialysis through an AV fistula, the buttonhole technique is used even though this technique is used among only 14% of patients with AV fistula.

Figure 6 – Breakdown of VARBSIs by Type of Vascular Access, Québec, 2016–2017 (N = 127)

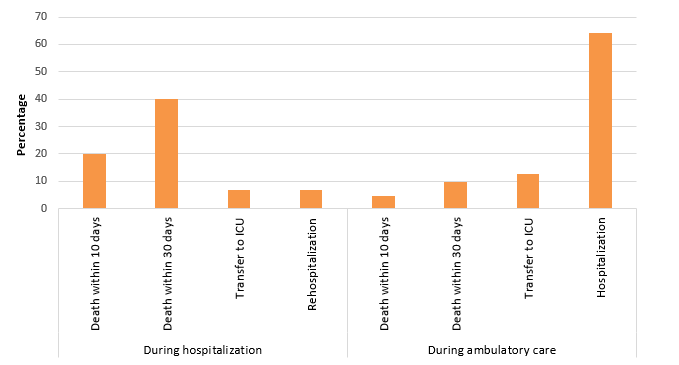

Overall, 13% of VARBSI cases resulted in death within 30 days following the onset of bacteremia. Death occurred in 40% of cases of VARBSI among hospitalized patients (Table 4 and Figure 7), compared with 10% of cases among patients receiving ambulatory care (p < 0.05). A total of 64% of ambulatory patients who developed a VARBSI required hospitalization.

Table 4 – 10-Day and 30-Day Case Fatality, Transfers to ICU and Hospitalizations and Rehospitalizations During a VARBSI Episode, by Origin of Acquisition, Québec, 2016–2017 (N, %)

| Origin of acquisition | Complication | Number of VARBSI cases monitored | Presence of complication | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

N | % | |||

| During hospitalization | Death within 10 days | 15 | 3 | 20 |

| Death within 30 days | 15 | 6 | 40 | |

| Transfer to ICU | 15 | 1 | 7 | |

| Rehospitalization | 15 | 1 | 7 | |

| During ambulatory care | Death within 10 days | 112 | 5 | 4 |

| Death within 30 days | 112 | 11 | 10 | |

| Transfer to ICU | 112 | 14 | 13 | |

| Hospitalization | 112 | 72 | 64 | |

Figure 7 – 10-Day and 30-Day Case Fatality, Percentage of Transfers to ICU and Percentage of Hospitalizations and Rehospitalizations During a VARBSI Episode, by Origin of Acquisition, Québec, 2016–2017 (%)

Microbiology

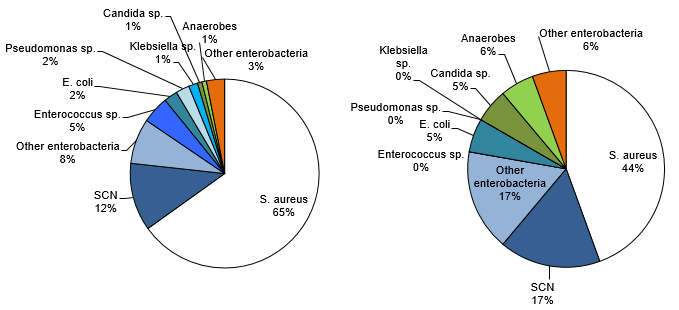

Figure 8 shows that Staphylococcus aureus is the most frequently isolated microorganism in all VARBSI cases (65%). It is followed by coagulase-negative Staphylococcus (CoNS, 12%) and enterobacteria (Escherichia coli, Klebsiella sp. and other enterobacteria, 12%). S. aureus is the most frequently isolated microorganism in cases resulting in death (44%).

Figure 8 – Categories of Isolated Microorganisms in All Reported Cases (N = 129) and Cases Resulting in Death Within 30 Days (N = 18), Québec, 2016–2017 (%)

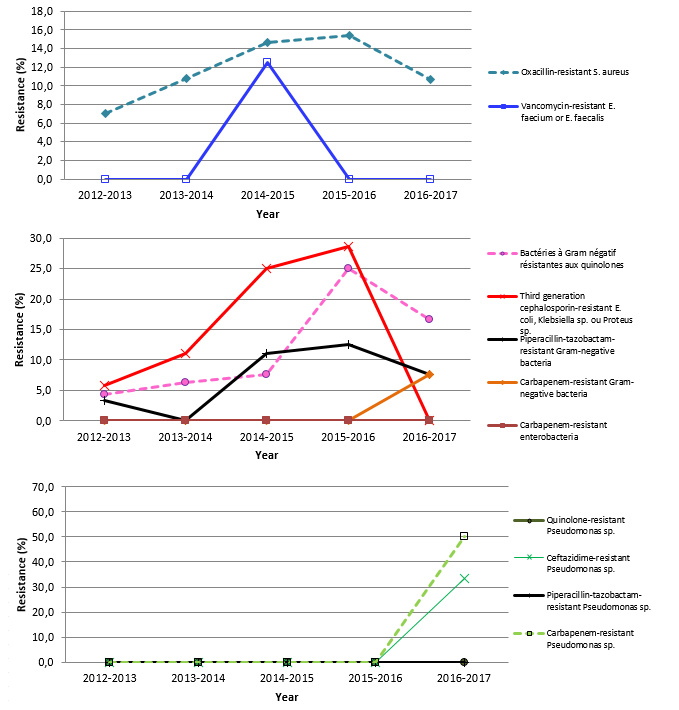

In 2016–2017, 11% of S. aureus strains are oxacillin-resistant, which is not significantly different compared with the 2012–2016 percentage (Table 5 and Figure 9). Please note that results presented in the second graph of Figure 9 exclude Pseudomonas sp.

Table 5 – Percentage of Strains Tested and Percentage of Resistance to Antibiotics for Certain Isolated Microorganisms, Québec, 2016–2017 (N, %)

| Microorganism | Antibiotic | Isolated | Tested | Resistant | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

N | N | % | N | % | ||

| Staphylococcus aureus | Oxacillin | 84 | 84 | 100 | 9 | 10.7 |

| Enterococcus faecium | Vancomycin | 0 | 0 | - | - | - |

| Enterococcus faecalis | Vancomycin | 5 | 5 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Klebsiella sp. | CSE 4 | 2 | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Imipenem ou meropenem | 2 | 1 | 50 | 0 | 0 | |

| Multiresistant 1 | 2 | 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 | |

| Escherichia coli | CSE 4 | 3 | 3 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Fluoroquinolones 3 | 3 | 3 | 100 | 0 | 0 | |

| Imipenem ou meropenem | 3 | 2 | 66.7 | 0 | 0 | |

| Multiresistant 1 | 3 | 3 | 100 | 0 | 0 | |

| Enterobacter sp. | CSE 4 | 5 | 5 | 100 | 2 | 40 |

| Imipenem ou meropenem | 5 | 4 | 80 | 0 | 0 | |

| Multiresistant 1 | 5 | 4 | 80 | 0 | 0 | |

| Pseudomonas sp. | Amikacin, gentamicin or tobramycin | 3 | 3 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| CSE 2 | 3 | 3 | 100 | 1 | 33.3 | |

| Fluoroquinolones 2 | 3 | 3 | 100 | 0 | 0 | |

| Imipenem ou meropenem | 3 | 2 | 66.7 | 1 | 50 | |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam | 3 | 3 | 100 | 0 | 0 | |

| Multiresistant 2 | 3 | 3 | 100 | 0 | 0 | |

| Acinetobacter sp. | Imipenem ou meropenem | 0 | 0 | - | - | - |

| Multiresistant 3 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | |

CSE 2: cefepime or ceftazidime;

CSE 4: cefepime, cefotaxime, ceftazidime or ceftriaxone;

Fluoroquinolones 2: ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin;

Fluoroquinolones 3: ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin or moxifloxacin;

Multiresistant 1: intermediate or resistant to an agent in three of the following five categories: cephalosporins 4, fluoroquinolones 3, aminoglycosides, carbapenems, piperacillin or piperacillin/tazobactam.

Multiresistant 2: intermediate or resistant to an agent in three of the following five categories: cephalosporins 2, fluoroquinolones 2, aminoglycosides, carbapenems, piperacillin or piperacillin/tazobactam.

Multiresistant 3: intermediate or resistant to an agent in three of the following six categories: cephalosporins 2, fluoroquinolones 2, aminoglycosides, carbapenems, piperacillin or piperacillin/tazobactam, ampicillin/sulbactam.

Figure 9 – Evolution of Percentage of Antibiotic Resistance in Certain Gram-Positive Bacteria, Certain Gram-Negative Bacteria and Pseudomonas sp., Québec, 2012-2016 to 2016–2017 (%)

Results per Healthcare Facility

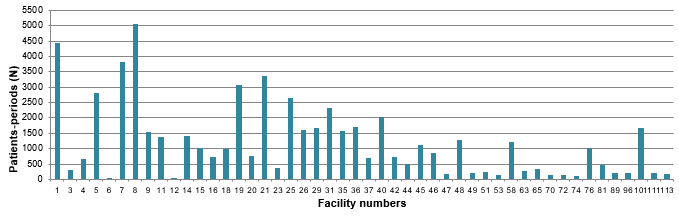

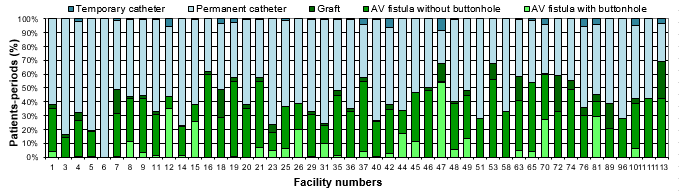

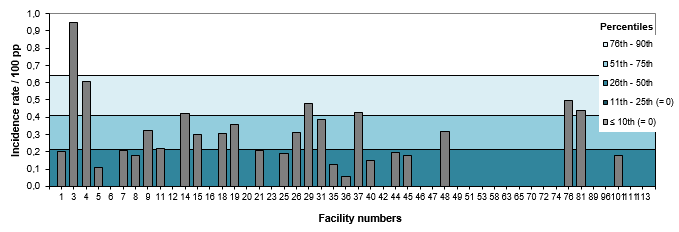

Figures 10 and 11 show the breakdown of patient-periods monitored in 2016–2017, by type of vascular access and by healthcare facility. In 2016–2017, the percentage of fistulas decreased in 15 healthcare facilities and increased in 8 (Table 6). Twenty-one facilities report a rate of 0 VARBSI per 100 patient-periods, and 1 facility (2% of facilities) reports a rate higher than the 90th-percentile mark for 2012–2016 (Figure 12 and Table 7). Facilities with an incidence rate of 0 have small dialysis units of 4 to 12 chairs, except for three larger units.

Figure 10 – Patient-periods Followed, by Healthcare Facility, Québec, 2016–2017 (%)

Figure 11 – Breakdown of Patient-periods Monitored by Type of Vascular Access and by Healthcare Facility, Québec, 2016–2017 (N)

Figure 12 – VARBSI Incidence Rate per Healthcare Facility (2016–2017) and Incidence Rate Percentile (2012–2013 to 2015–2016), Québec, 2016–2017 (Incidence Rate per 100 Patient-periods)

Table 6 – Evolution of the Number of Patient-Periods Monitored and Percentage of Fistulas, by Healthcare Facility, Québec, 2012–2016 and 2016–2017 (N, % [95% CI])

| Facility | 2012-2016 | 2016-2017 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Patient-periods (N) | % with fistula | Patient-periods (N) | % with fistula | Variation (p<0.05) | ||

| 1 | HÔPITAL CHARLES LEMOYNE | 1,6571 | 37 [37 ; 38] | 4,454 | 38 [37 ; 40] | |

| 3 | GLEN - ROYAL VICTORIA | 6,367 | 42 [41 ; 43] | 316 | 16 [12 ; 21] | decrease |

| 4 | HÔPITAL NOTRE-DAME DU CHUM | 9,202 | 63 [62 ; 64] | 661 | 33 [29 ; 36] | decrease |

| 5 | HÔPITAL GÉNÉRAL JUIF | 10,680 | 21 [20 ; 22] | 2,829 | 19 [18 ; 21] | decrease |

| 6 | GLEN - ENFANTS | 169 | 27 [21 ; 34] | 17 | 0 | decrease |

| 7 | PAVILLON L'HÔTEL-DIEU DE QUÉBEC | 15,144 | 54 [54 ; 55] | 3,811 | 49 [47 ; 50] | decrease |

| 8 | PAVILLON MAISONNEUVE/PAVILLON MARCEL-LAMOUREUX | 19,732 | 44 [43 ; 45] | 5,054 | 44 [42 ; 45] | |

| 9 | HÔPITAL DU HAUT-RICHELIEU | 6,145 | 43 [42 ; 44] | 1,543 | 45 [42 ; 47] | |

| 11 | HÔPITAL PIERRE-LE GARDEUR | 4,499 | 40 [38 ; 41] | 1,378 | 33 [31 ; 36] | decrease |

| 12 | CENTRE HOSPITALIER UNIVERSITAIRE SAINTE-JUSTINE | 246 | 26 [21 ; 31] | 34 | 44 [27 ; 61] | increase |

| 14 | CENTRE HOSPITALIER RÉGIONAL DE LANAUDIÈRE | 4,984 | 25 [23 ; 26] | 1,423 | 23 [21 ; 25] | |

| 15 | HÔPITAL FLEURIMONT | 4,713 | 32 [31 ; 33] | 1,008 | 38 [35 ; 41] | increase |

| 16 | HÔPITAL RÉGIONAL DE RIMOUSKI | 2,798 | 58 [56 ; 60] | 723 | 62 [58 ; 66] | increase |

| 18 | HÔTEL-DIEU DE LÉVIS | 4,314 | 46 [45 ; 48] | 989 | 49 [46 ; 52] | |

| 19 | HÔPITAL CITÉ DE LA SANTÉ | 12,058 | 64 [64 ; 65] | 3,074 | 58 [56 ; 59] | decrease |

| 20 | HÔPITAL DE CHICOUTIMI | 3,948 | 51 [49 ; 52] | 776 | 38 [35 ; 41] | decrease |

| 21 | HÔPITAL SAINT-LUC DU CHUM | 5,396 | 59 [58 ; 60] | 3,359 | 58 [56 ; 59] | |

| 23 | HÔTEL-DIEU D'ARTHABASKA | 1,140 | 29 [27 ; 32] | 365 | 24 [19 ; 28] | decrease |

| 25 | HÔPITAL DU SACRÉ-COEUR DE MONTRÉAL | 9,837 | 32 [31 ; 33] | 2,639 | 37 [35 ; 39] | increase |

| 26 | HÔPITAL DE VERDUN | 6,700 | 42 [41 ; 43] | 1,610 | 39 [37 ; 41] | decrease |

| 29 | HÔPITAL GÉNÉRAL DE MONTRÉAL | 5,786 | 33 [32 ; 34] | 1,667 | 33 [31 ; 35] | |

| 31 | PAVILLON SAINTE-MARIE | 8,353 | 28 [27 ; 29] | 2,320 | 24 [23 ; 26] | decrease |

| 35 | HÔPITAL HONORÉ-MERCIER | 4,700 | 53 [51 ; 54] | 1,580 | 48 [46 ; 51] | decrease |

| 36 | HÔPITAL GÉNÉRAL DU LAKESHORE | 5,846 | 34 [33 ; 35] | 1,708 | 35 [33 ; 37] | |

| 37 | HÔTEL-DIEU DE SOREL | 2,650 | 57 [55 ; 59] | 705 | 57 [54 ; 61] | |

| 40 | HÔPITAL DE HULL | 8,824 | 29 [28 ; 30] | 2,021 | 26 [24 ; 28] | decrease |

| 42 | CENTRE HOSPITALIER ANNA-LABERGE | - | - | 724 | 38 [34 ; 42] | |

| 44 | HÔPITAL SAINTE-CROIX | 1,986 | 39 [37 ; 41] | 517 | 34 [30 ; 38] | decrease |

| 45 | HÔPITAL DE SAINT-EUSTACHE | - | - | 1,118 | 47 [44 ; 50] | |

| 46 | HÔPITAL DE GRANBY | 2,690 | 51 [49 ; 53] | 858 | 50 [47 ; 53] | |

| 47 | HÔPITAL DE ROUYN-NORANDA | 611 | 74 [71 ; 78] | 181 | 67 [61 ; 74] | |

| 48 | CENTRE HOSPITALIER DE ST. MARY | 4,575 | 43 [41 ; 44] | 1,270 | 40 [37 ; 43] | |

| 49 | CSSS DE MEMPHREMAGOG | 766 | 46 [42 ; 49] | 200 | 48 [41 ; 55] | |

| 51 | HÔPITAL DE MANIWAKI | 873 | 33 [30 ; 37] | 238 | 28 [22 ; 34] | |

| 53 | HÔPITAL DE CHANDLER | 236 | 55 [49 ; 61] | 147 | 68 [60 ; 76] | increase |

| 58 | HÔPITAL DU SUROÎT | 4,172 | 51 [49 ; 52] | 1,224 | 33 [31 ; 36] | decrease |

| 63 | HÔPITAL DE SAINT-GEORGES | 862 | 54 [51 ; 57] | 278 | 58 [52 ; 64] | |

| 65 | HÔPITAL ET CLSC DE VAL-D'OR | 1,551 | 44 [41 ; 46] | 348 | 54 [49 ; 60] | increase |

| 70 | CENTRE DE SOINS DE COURTE DURÉE LA SARRE | 429 | 55 [50 ; 60] | 143 | 60 [52 ; 68] | |

| 72 | HÔPITAL ET CENTRE D'HÉBERGEMENT DE SEPT-ÎLES | 540 | 63 [59 ; 67] | 153 | 59 [51 ; 67] | |

| 74 | HÔPITAL DE DOLBEAU-MISTASSINI | 399 | 37 [32 ; 42] | 128 | 55 [47 ; 64] | increase |

| 76 | HÔPITAL DE LACHINE | - | - | 1,009 | 36 [33 ; 39] | |

| 81 | HÔPITAL DE MONT-LAURIER | 1,701 | 49 [47 ; 52] | 457 | 46 [41 ; 50] | |

| 89 | HÔPITAL DE MONTMAGNY | 349 | 41 [36 ; 46] | 199 | 39 [32 ; 45] | |

| 96 | CENTRE DE SANTÉ DE CHIBOUGAMAU | 953 | 32 [29 ; 35] | 225 | 28 [22 ; 34] | |

| 101 | HÔPITAL RÉGIONAL DE SAINT-JÉRÔME | 9,267 | 44 [43 ; 45] | 1,688 | 43 [40 ; 45] | |

| 111 | HÔPITAL DE PAPINEAU | 468 | 37 [32 ; 41] | 223 | 42 [36 ; 49] | |

| 113 | HÔPITAL DE THETFORD MINES | 783 | 59 [56 ; 63] | 178 | 69 [62 ; 76] | increase |

Table 7 – Evolution of the Number of VARBSI Cases and Incidence Rate by Healthcare Facility, Québec,

2012–2016 and 2016–2017 (Incidence Rate per 100 Patient-periods [95% CI])

| Facility | 2012-2016* | 2016-2017 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Cases (N) | Cases per year (N) | Rate /100 pp | Cases (N) | Rate /100 pp | ||

| 1 | HÔPITAL CHARLES LEMOYNE | 38 | 9.5 | 0.23 [0.16 ; 0.31] | 9 | 0.20 [0.09 ; 0.36] |

| 3 | GLEN - ROYAL VICTORIA | 36 | 9 | 0.57 [0.40 ; 0.77] | 3 | 0.95 [0.18 ; 2.33] |

| 4 | HÔPITAL NOTRE-DAME DU CHUM | 47 | 11.8 | 0.51 [0.38 ; 0.67] | 4 | 0.61 [0.16 ; 1.34] |

| 5 | HÔPITAL GÉNÉRAL JUIF | 16 | 4 | 0.15 [0.09 ; 0.23] | 3 | 0.11 [0.02 ; 0.26] |

| 6 | GLEN - ENFANTS | 0 | 0 | 0.00 [0.57 ; 0.57] | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | PAVILLON L'HÔTEL-DIEU DE QUÉBEC | 46 | 11.5 | 0.30 [0.22 ; 0.40] | 8 | 0.21 [0.09 ; 0.38] |

| 8 | PAVILLON MAISONNEUVE/PAVILLON MARCEL-LAMOUREUX | 63 | 15.8 | 0.32 [0.25 ; 0.40] | 9 | 0.18 [0.08 ; 0.31] |

| 9 | HÔPITAL DU HAUT-RICHELIEU | 16 | 4 | 0.26 [0.15 ; 0.40] | 5 | 0.32 [0.10 ; 0.67] |

| 11 | HÔPITAL PIERRE-LE GARDEUR | 18 | 4.5 | 0.40 [0.24 ; 0.61] | 3 | 0.22 [0.04 ; 0.53] |

| 12 | CENTRE HOSPITALIER UNIVERSITAIRE SAINTE-JUSTINE | 8 | 2 | 3.25 [1.39 ; 5.90] | 0 | 0 |

| 14 | CENTRE HOSPITALIER RÉGIONAL DE LANAUDIÈRE | 12 | 3 | 0.24 [0.12 ; 0.40] | 6 | 0.42 [0.15 ; 0.83] |

| 15 | HÔPITAL FLEURIMONT | 22 | 5.5 | 0.47 [0.29 ; 0.68] | 3 | 0.30 [0.06 ; 0.73] |

| 16 | HÔPITAL RÉGIONAL DE RIMOUSKI | 4 | 1 | 0.14 [0.04 ; 0.32] | 0 | 0 |

| 18 | HÔTEL-DIEU DE LÉVIS | 4 | 1 | 0.09 [0.02 ; 0.21] | 3 | 0.30 [0.06 ; 0.74] |

| 19 | HÔPITAL CITÉ DE LA SANTÉ | 23 | 5.8 | 0.19 [0.12 ; 0.28] | 11 | 0.36 [0.18 ; 0.60] |

| 20 | HÔPITAL DE CHICOUTIMI | 10 | 2.5 | 0.25 [0.12 ; 0.43] | 0 | 0 |

| 21 | HÔPITAL SAINT-LUC DU CHUM | 20 | 6.7 | 0.37 [0.23 ; 0.55] | 7 | 0.21 [0.08 ; 0.39] |

| 23 | HÔTEL-DIEU D'ARTHABASKA | 1 | 0.3 | 0.09 [0.00 ; 0.34] | 0 | 0 |

| 25 | HÔPITAL DU SACRÉ-COEUR DE MONTRÉAL | 39 | 9.8 | 0.40 [0.28 ; 0.53] | 5 | 0.19 [0.06 ; 0.39] |

| 26 | HÔPITAL DE VERDUN | 19 | 4.8 | 0.28 [0.17 ; 0.43] | 5 | 0.31 [0.10 ; 0.64] |

| 29 | HÔPITAL GÉNÉRAL DE MONTRÉAL | 21 | 5.3 | 0.36 [0.22 ; 0.53] | 8 | 0.48 [0.20 ; 0.87] |

| 31 | PAVILLON SAINTE-MARIE | 22 | 5.5 | 0.26 [0.16 ; 0.38] | 9 | 0.39 [0.18 ; 0.68] |

| 35 | HÔPITAL HONORÉ-MERCIER | 16 | 4 | 0.34 [0.19 ; 0.53] | 2 | 0.13 [0.01 ; 0.36] |

| 36 | HÔPITAL GÉNÉRAL DU LAKESHORE | 11 | 2.8 | 0.19 [0.09 ; 0.32] | 1 | 0.06 [0.00 ; 0.23] |

| 37 | HÔTEL-DIEU DE SOREL | 15 | 3.8 | 0.57 [0.32 ; 0.89] | 3 | 0.43 [0.08 ; 1.04] |

| 40 | HÔPITAL DE HULL | 28 | 7 | 0.32 [0.21 ; 0.45] | 3 | 0.15 [0.03 ; 0.36] |

| 42 | CENTRE HOSPITALIER ANNA-LABERGE | - | - | - | 0 | 0 |

| 44 | HÔPITAL SAINTE-CROIX | 6 | 1.5 | 0.30 [0.11 ; 0.59] | 1 | 0.19 [0.00 ; 0.76] |

| 45 | HÔPITAL DE SAINT-EUSTACHE | - | - | - | 2 | 0.18 [0.02 ; 0.51] |

| 46 | HÔPITAL DE GRANBY | 6 | 1.5 | 0.22 [0.08 ; 0.44] | 0 | 0 |

| 47 | HÔPITAL DE ROUYN-NORANDA | 1 | 0.3 | 0.16 [0.00 ; 0.64] | 0 | 0 |

| 48 | CENTRE HOSPITALIER DE ST. MARY | 7 | 1.8 | 0.15 [0.06 ; 0.29] | 4 | 0.31 [0.08 ; 0.70] |

| 49 | CSSS DE MEMPHREMAGOG | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 51 | HÔPITAL DE MANIWAKI | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 53 | HÔPITAL DE CHANDLER | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 58 | HÔPITAL DU SUROÎT | 8 | 2 | 0.19 [0.08 ; 0.35] | 0 | 0 |

| 63 | HÔPITAL DE SAINT-GEORGES | 1 | 0.3 | 0.12 [0.00 ; 0.45] | 0 | 0 |

| 65 | HÔPITAL ET CLSC DE VAL-D'OR | 8 | 2 | 0.52 [0.22 ; 0.94] | 0 | 0 |

| 70 | CENTRE DE SOINS DE COURTE DURÉE LA SARRE | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 72 | HÔPITAL ET CENTRE D'HÉBERGEMENT DE SEPT-ÎLES | 2 | 0.5 | 0.37 [0.03 ; 1.06] | 0 | 0 |

| 74 | HÔPITAL DE DOLBEAU-MISTASSINI | 2 | 0.7 | 0.50 [0.05 ; 1.44] | 0 | 0 |

| 76 | HÔPITAL DE LACHINE | - | - | - | 5 | 0.50 [0.16 ; 1.03] |

| 81 | HÔPITAL DE MONT-LAURIER | 4 | 1 | 0.24 [0.06 ; 0.52] | 2 | 0.44 [0.04 ; 1.25] |

| 89 | HÔPITAL DE MONTMAGNY | 2 | 1 | 0.57 [0.05 ; 1.64] | 0 | 0 |

| 96 | CENTRE DE SANTÉ DE CHIBOUGAMAU | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 101 | HÔPITAL RÉGIONAL DE SAINT-JÉRÔME | 35 | 8.8 | 0.38 [0.26 ; 0.51] | 3 | 0.18 [0.03 ; 0.44] |

| 111 | HÔPITAL DE PAPINEAU | 2 | 1 | 0.43 [0.04 ; 1.22] | 0 | 0 |

| 113 | HÔPITAL DE THETFORD MINES | 3 | 0.8 | 0.38 [0.07 ; 0.94] | 0 | 0 |

*Changes in rates within individual facilities were not subjected to statistical analysis, given the small number of cases involved.

References

- Fistula First. Graphs of Prevalent AV Fistula Use Rates, By Network [online]. http://www.fistulafirst.org/AboutFistulaFirst/FisultaFirstCatheterLastFFCLData.aspx (last consulted: 2013-08-06).

- Ayzac, L., Machut, A., Russell, I., et al. Rapport final pour l’année 2011 du réseau de surveillance des infections en hémodialyse – DIALIN. CClin Sud-Est and RAISIN [online]. http://cclin-sudest.chu-lyon.fr/Reseaux/DIALIN/Resultats/rapport_annuel_2011_V2.pdf (last consulted: 2013-08-06).

- Patel, P. R., Yi, S. H., Booth, S., et al. Bloodstream Infection Rates in Outpatient Hemodialysis Facilities Participating in a Collaborative Prevention Effort: A Quality Improvement Report. American Journal of Kidney Diseases, Vol. 62, No. 2 (August 2013), p. 322–330.

Author

Comité de surveillance provinciale des infections nosocomiales (SPIN) – bactériémies associées aux accès vasculaires en hémodialyse

Editorial Committee

Élise Fortin, Direction des risques biologiques et de la santé au travail, Institut national de santé publique du Québec

Charles Frenette, Centre universitaire de santé McGill

Muleka Ngenda-Muadi, Direction des risques biologiques et de la santé au travail, Institut national de santé publique du Québec

Isabelle Rocher, Direction des risques biologiques et de la santé au travail, Institut national de santé publique du Québec

Claude Tremblay, Centre hospitalier universitaire de Québec de Québec – Université Laval

Mélissa Trudeau, Direction des risques biologiques et de la santé au travail, Institut national de santé publique du Québec

Jasmin Villeneuve, Direction des risques biologiques et de la santé au travail, Institut national de santé publique du Québec

![Figure 1 – VARBSI Incidence Rate by Type of Vascular Access, Québec, 2016–2017 (Incidence Rate per 100 Patient-periods [95% CI]) Figure 1 – VARBSI Incidence Rate by Type of Vascular Access, Québec, 2016–2017 (Incidence Rate per 100 Patient-periods [95% CI])](/sites/default/files/images/maladies-infectieuses/spin/hd/2017/en/figure1.png)

![Figure 3 – Evolution of VARBSI Incidence Rates by Type of Vascular Access in Units That Have Previously Participated (N=45), Québec, 2012–2016 and 2016–2017 (Incidence Rate per 100 Patient-Periods [95% CI]) Figure 3 – Evolution of VARBSI Incidence Rates by Type of Vascular Access in Units That Have Previously Participated (N=45), Québec, 2012–2016 and 2016–2017 (Incidence Rate per 100 Patient-Periods [95% CI])](/sites/default/files/images/maladies-infectieuses/spin/hd/2017/en/figure3.png)