Is it a tick?

Is the arthropod I collected a tick?

The tick attaches to its host

Ticks spend a part of their lifecycle on the ground and another part attached to the skin of their host, feeding on their blood. The meal usually lasts for 3 to 10 days and the tick only detaches from the host at the very end of the meal to drop to the ground. During the meal, ticks attach very strongly to the skin. In Québec, there are very few, if any, insects or other arthropods that remain so strongly attached to the skin of humans for over 24 hours.

If you discover an arthropod that has been strongly anchored to the skin for some time, this is a good indication that it is a tick.

Ticks are not insects

Unlike the majority of insects, ticks have four pairs of legs rather than three (except in the larval stage), they have neither wings nor antennae and their bodies are not segmented into three parts. Only two parts can be distinguished: the anterior section or “capitulum” (Latin for “head”) and the posterior section or “idiosoma” (from the Latin for “abdomen”).

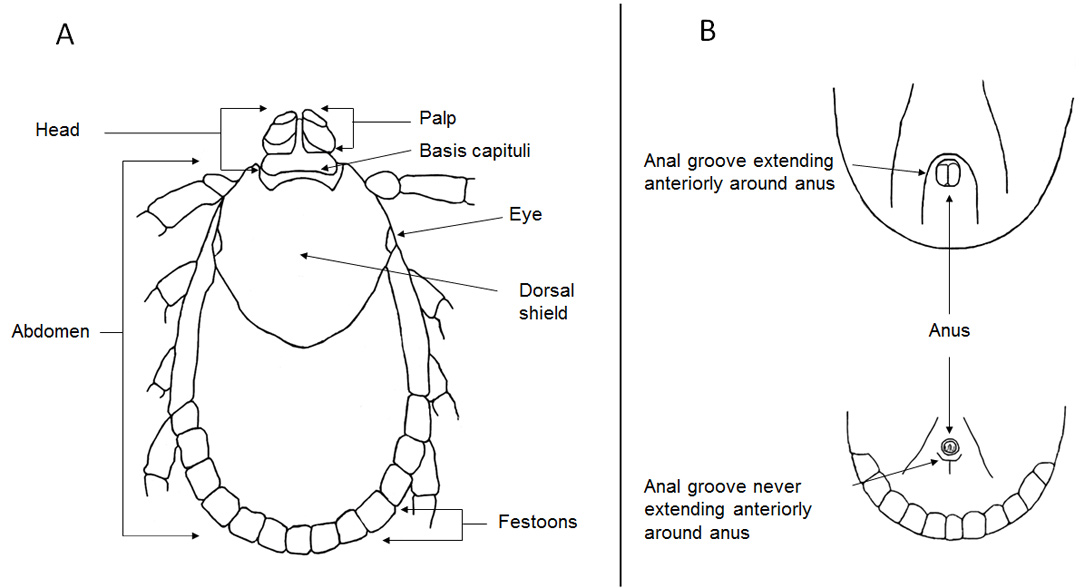

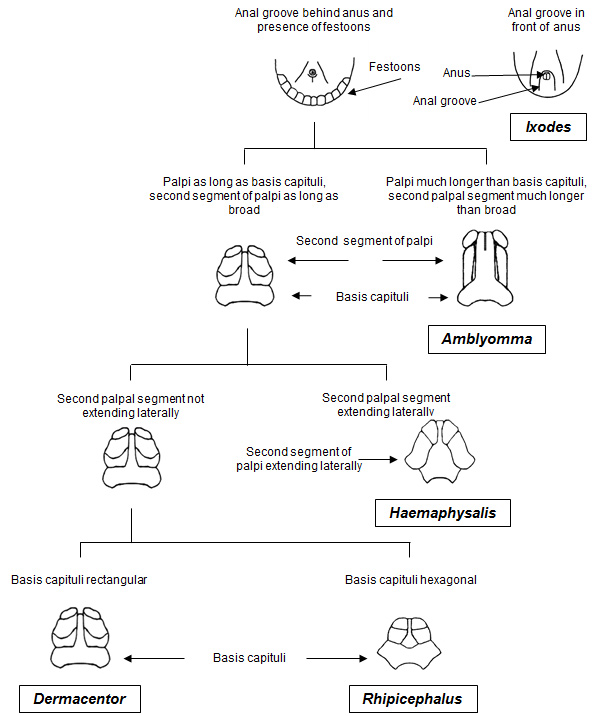

Morphological criteria essential to the identification of different tick genera

A minimum of knowledge is required to identify the different tick species present in Québec. The following image shows the different morphological criteria used in this guide.

Ticks go through four stages of development

Prior to identifying a tick, it is necessary to determine its stage of development as identification criteria may vary from one stage to another. All tick species go through four distinct evolutionary stages:

- Egg (not shown below)

- Larva

- Nymph

- Adult (male and female)

Different stages of the Ixodes scapularis tick (ventral surface).

- Larva: The larva has only 3 pairs of legs, whereas during the other stages ticks have 4 pairs. It is very small and usually measures less than one millimetre.

- Nymph: The nymph has 4 pairs of legs and differs from adults by the absence of a genital pore. The genital pore is only present in the female and the male.

- Female: The female has 4 pairs of legs and a genital pore. The female’s shield (or scutum) is partial and does not cover the whole tick.

- Male: Like the female, the male has a genital pore, but its shield (line 3) is complete (it covers the whole tick).

The size of a tick can vary

The detection and examination of ticks is difficult given their small size: the length of larvae and nymphs rarely exceeds one millimetre while that of adults varies from 3 to 5 mm depending on the species. Adult females engorged with blood are the most identifiable as their size can reach between 8 and 13 mm depending on the species.

Levels of engorgement

Ticks can be found at different levels of engorgement depending on how long they have been attached to a host and feeding. A tick’s weight can increase 100 fold during a blood meal—in other words, it can get a lot bigger. Tick engorgement can make identification more difficult for inexperienced people. On the other hand, once we know what identification criteria to look for, we see that these remain unchanged regardless of the level of engorgement and that identification can still be easily achieved.