On this page :

Frequently asked questions

From a public health perspective, the criminalization of people who use drugs on the account of simple possession is one of the main challenges that current drug policies must address. In some cases, criminalization and its related practices are known to hinder different public health measures, especially those aiming to manage the ongoing overdose crisis or to reduce the transmission of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and other blood-borne and sexually transmitted diseases. Stigmatization, which particularly affects marginalized consumers both socially and economically, is also an important factor to consider when elaborating alternative approaches. When considered, it is likely to mitigate some adverse effects of the current prohibition framework.

In general, there has been a shift in perspective and it is now more widely accepted that substance use should be approached from a public health perspective rather than one of public safety or justice. This has led to alternatives to criminalization.

Below, the Institut national de santé publique du Québec (INSPQ) answers key questions on this topic. Their answers are based on the scientific literature and on two recent reports requested by the Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux (MSSS).

Some conceptual clarifications

1. How is the decriminalization of simple possession of drugs defined?

To begin, “simple possession of drugs” is a legal concept that must be distinguished from “possession with intent to distribute.” The former, refers to the possession of a small quantity of drugs for personal use.

The Juridictionnaire provides two Canadian definitions of this term(decriminalization). The first considers decriminalization “as a process that reduces the severity of an offence or eliminates the criminal nature of an act” [translated from the French]. The second defines it as “the action of removing an act or omission that was previously considered a criminal offence from criminal jurisdiction” [translated from the French]1.

In other words, decriminalization refers to initiatives that generally avoid (fully or partly) the application of criminal sanction for such offense. These initiatives can either be de facto (the offence remains in the Criminal Code, but civil penalties such as fines may replace criminal penalties) or de jure (the offence is removed from the Criminal Code).

However, this term is generally used in a different context than one applicable to drugs. It is often poorly defined by different actors and used incorrectly or imprecisely, which leads to further confusion. At least four decriminalization models can be identified:

- The imposition of a civil penalty (e.g., a fine), while removing the sanction from the Criminal Code (de jure), like in the Czech Republic. This would allow for the offense of simple possession to be addressed similarly to an offense under the Highway Safety Code.

- The addition of a ticketing scheme, without removing the criminal sanction (de facto approach, as is applied in some Australian states). This model may also include established eligibility criteria and scaled severity sanctions (the severity increasing after a first or second police arrest for example).

- The non-use of criminal sanctions and the implementation of diversion pathways, which means a procedure to redirect people onto health or social services. This process may be de jure (e.g., Portugal) or de facto (e.g., the LEAD Program in the United States). Some jurisdictions can also impose a civil or administrative penalty (e.g., fine, suspension of licence), as is done in Portugal.

- The deprioritization of police interventions or prosecutors’ practices (de facto), without sanctions or diversion pathways. The Netherlands’ “tolerance policy” on cannabis is an example. This deprioritization applies to the instructions given to police officers with the aim to move away from interventions for people who use drugs. It also applies to those issued by the federal government in 2020, to encourage prosecutors to reduce or cease their involvement in simple possession cases. It does not apply to those presenting a threat to public safety.

1Refer to: https://www.btb.termiumplus.gc.ca/juridi-srch?lang=fra&srchtxt=d%C3%A9criminalisation&i=&lettr=indx_catlog_d&cur=1&nmbr=&comencsrch.x=0&comencsrch.y=0 (last consulted December 6, 2021).

2. Are legalization and decriminalization the same?

No. It is difficult to briefly explain all the differences between these two terms. When we talk about legalization, we are referring to removing the general prohibitions concerning a substance’s production, distribution, and consumption. As is the case in Québec and Canada for cannabis, alcohol, and tobacco, legalization also involves implementing a legal and regulatory framework within which certain activities are permitted under certain conditions. Legalization therefore does not mean that possession is not prohibited under penal or criminal law.

For example, under the federal Cannabis Act, it is currently prohibited to possess more than 30 grams of dry cannabis or its equivalent in a public space, even when this substance is intended for personal use. Possession of a higher quantity of the substance can lead to a criminal sanction. There are also various bans applying to any quantity under Québec’s Cannabis Regulation Act. For example, regarding cannabis in Québec, a person whose work requires that they provide care for a child, a senior, or an individual in a vulnerable situation may not use this substance during the hours in which they actively provide these services.

To better understand what is meant by decriminalization, refer to question 1.

The regulatory framework may apply to a substance’s production, distribution, sale, and consumption. In a decriminalization context, activities related to production, distribution, and sale are usually not regulated.

Interactions with law enforcement

3. How many people are arrested for simple possession of drugs in Québec each year?

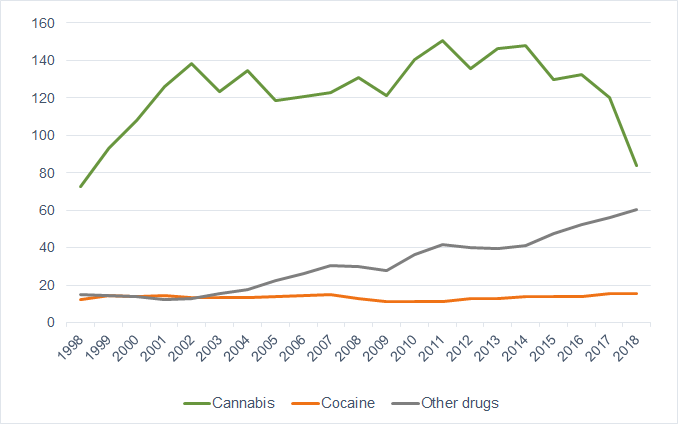

Between 1998 and 2018, an average of 13,198 tickets were issued per year for simple possession of drugs in Québec. More specifically, 79% of these tickets were issued for cannabis, either for simple possession or for consumption.

On average, 36 people per day across Québec are arrested for simple possession of drugs. Of these people, eight arrests are for the possession of substances other than cannabis (e.g., heroin, cocaine, ecstasy, MDMA).

There is, however, a significant limitation to these data: they do not specify whether the tickets were issued only for simple possession or in combination with other infractions or offences.

Incidentally, substance use recidivism is a significant phenomenon. While there are no local statistical data specifically on people who use drugs recidivism, police interventions often involve the same individuals. This means the number of different people receiving tickets for simple possession of drugs is probably much smaller than the total number of tickets issued.

Evolution of rates of individuals charged for simple possession of drugs in Québec, by substance, per 100,000 population, 1998-2018

Clarification: “other drugs” include heroin, methamphetamines, methylenedioxymethamphetamine, other opioids, and other drugs subject to the Act.

Data source: Statistics Canada. Table 35-10-0177-01: Incident-based crime statistics, by detailed violations, Canada, provinces, territories and Census Metropolitan Areas.

4. Has cannabis legalization led to a significant decrease in the number of people arrested for simple possession of drugs?

Data on this topic are not yet available. However, since the simple possession of a small quantity of cannabis for personal use has been legal for individuals 21 years of age or older in Québec as of late 2018, it seems clear that the total number (i.e., for all substances) of tickets should fall drastically. We should note that from 1998 to 2018, an average of 79% of all tickets for simple possession or consumption of drugs were issued for this substance.

Despite the legalization of cannabis, its consumption remains a criminal offence (that can lead to a criminal record) if done in a public space. A new provincial law also stipulates that a ticket may be given if a person under 21 years of age in possession of this substance is arrested by police, or if it is used in places prohibited by law.

5. It often seems that people arrested by the police have committed more than one offense at a time. Is this generally the case for people arrested for simple possession of drugs?

A police stop and a police arrest are two different processes. A police stop, also known as a street stop or street check, simply refers to the contact that a police officer may have with an individual to seek information without necessarily giving a sanction. An arrest takes place during police stop when police officers ascertain that a law has been broken. While we do not have statistical data to answer this specific question, it appears that arrests are frequently for more than just simple possession of drugs. A single arrest can in fact be for multiple charges. For example, someone may draw the attention of police for their behaviour under the influence of psychoactive substances, for their lifestyle (e.g., living in the public space), or because they are involved in illicit economic activities to support their consumption. Consequently, it is probable that, even though the law has been amended and simple possession no longer constitutes a criminal act, people who use drugs may continue to be arrested.

6. How many convictions for simple possession of drugs occur in Québec each year?

Generally speaking, trials exclusively for simple possession of drugs are fairly rare.

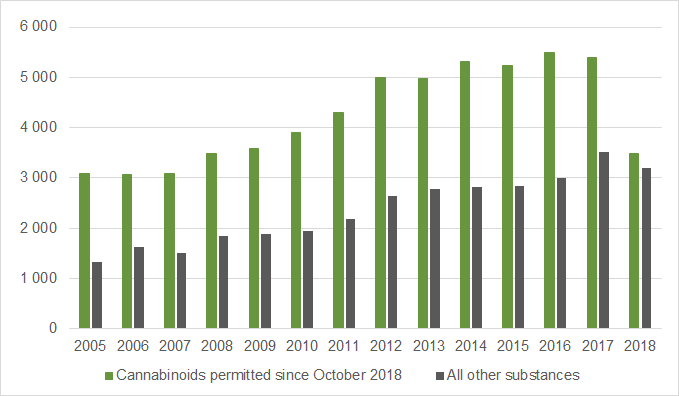

Data available from the Court of Québec indicate that the number of cases for simple possession offenses increased from 4,416 to 8,900 between 2005 and 2017 for all illicit substances.

Until 2017, simple possession of cannabis constituted an average of 65% of cases, while this proportion decreased to around 52% in 2018 (the year cannabis was legalized). The fact that it was legalized only in late 2018 explains the percentage still being high that year.

It is important to note that one case may include numerous charges and one person may be the subject of numerous cases. However, simple possession charges are usually dismissed if the accused pleads guilty to a more severe simultaneous charge through negotiations with a prosecutor.

Causes of infractions for simple possession alone, leading to conviction at the Court of Québec. Québec, 2005-2018

Data source: Plumitif M013 system — Gestion des causes criminelles adulte. Extraction date: 2020 09 22.

Public health and public safety: two reconcilable approaches?

7. What are the objectives of police and of healthcare workers in their interventions with people who use drugs?

The police and healthcare and social services professionals who work with people who use drugs intervene according to different logics.

Under section 48 of the Police Act, police officers are bound to “maintain peace, order and public security, to prevent and repress crime” [translated from the French]. Thus, their interventions may also include reducing actions that violate public order to a minimum, limiting the presence of people who are causing a so-called “disturbance” in public spaces, or ensuring that injection equipment is not left in parks or other public spaces. Reducing the presence of people occupying the public space and using drugs by enforcing the law may therefore be a strategy to make safer communities and to carry out their mission.

Public health interventions aim to reduce the harmful health effects associated with drug use. This can include encouraging people to consume more safely by adopting habits like: acquiring sterile injection and inhalation equipment, going to a supervised consumption site, carrying naloxone, avoiding using drugs alone, having their substances analyzed, as well as using existing services to improve their socioeconomic status or other factors that may be associated with drug use (e.g., mental health problems, economic insecurity, housing problems, lack of social support).

As demonstrated in an 2013 INSPQ synthesis [available in French only], in some cases, measures that are considered effective at preventing and reducing crime may also limit the ability to take preventative actions aiding people who use drugs. For example, police presence in some areas means that people who use drugs will make less use of harm reduction services for fear of being arrested by law enforcement.

8. Can public safety and of public health objectives coexist?

Certainly. Police and of public health professionals have complementary roles in regard to drug use. Practices of public safety actors are heeding the realities, needs, and challenges faced by people who use drugs. This observation was made by the INSPQ in a previous publication [available in French only]. Along the same line, in 2020, 13,000 chiefs of police in Canada took a position on the need for interventions other than criminalization for simple possession of drugs, including redirecting people to health care and social services.

In Québec, there has also been an emergence of collaborative initiatives between public safety and healthcare actors. For example, cross-sector teams were set up to promote joint intervention. Refer to the SPVM initiative: ÉMRII and another in Sherbrooke: EMIP.

In other cities, agreements have been made to limit police interventions around areas frequented by people who use drugs. In the last few years, an increasing number of police forces have trained their officers to administer naloxone, an antidote that can temporarily reverse the effects of an opioid overdose.

These different examples demonstrate that the goals of public safety and public health interventions, even if different, can be reconciled.

The costs of illicit substances in Québec

9. Are there data that can be used to estimate the costs related to psychoactive substance use?

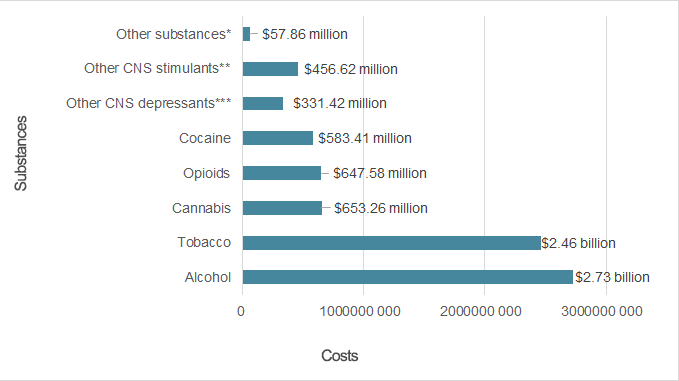

Yes. The Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction and the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research produce estimates including costs related to the criminal justice system, health care, productivity losses, and “other costs” (i.e., employee assistance programs, screening programs, the administrative costs of work accident compensation).

In 2017, the costs attributable to the use of psychoactive substances (for all substances combined) were estimated at $7.9 billion. Psychoactive substances considered “licit” generate the highest costs. As a comparison, and as displayed in the following figure for the same year, the cost related to alcohol use in Québec was $2.7 billion, while tobacco was associated with $2.5 billion in costs, and cannabis, $653.3 million.

In 2017, the estimated costs for illicit substances specifically (opioids, cocaine, depressants, stimulants, and “other substances”) were $2.1 billion.

In sum, 27% of the total cost related to the use of psychoactive substances is attributable to illicit substances. However, the number of people that use these substances is much lower than that of people who consume tobacco, alcohol, or cannabis.

Estimate of the overall total costs attributable to the use of psychoactive substances. Québec, 2017

*Hallucinogens, inhalants, etc.

**Amphetamines, methamphetamines, etc. Excludes cocaine.

***Benzodiazepines, barbiturates, etc. Excludes opioids and alcohol.

Date source: Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction and Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research (2017), Canadian Substance Use Costs and Harms Report.

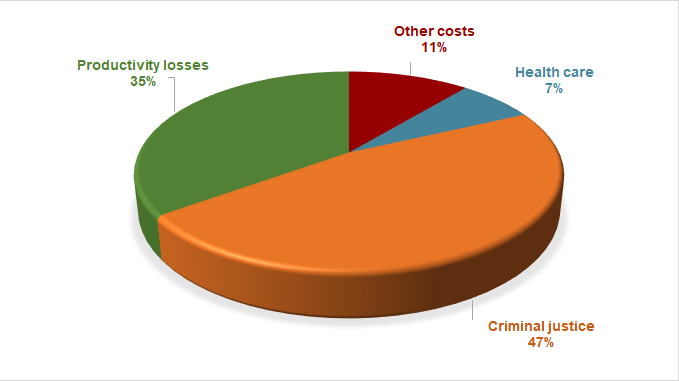

10. How are the costs associated with illicit substance use in Québec distributed?

In 2017, the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction and the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research estimated that 47% of costs attributable to illicit substance use in Québec are associated with the criminal justice system. These costs only include legal proceedings and correctional services. They do not include the estimated costs of police interventions.

The figure below shows that the costs associated with lost productivity are second highest (35%) while "other costs” (research and prevention, employee assistance programs, damages caused by fire, and administration for work accident compensation) are estimated at 11%. The costs associated with health care (including specialized treatment, doctors’ compensation, and prescription medications, but excluding hospitalizations, day surgeries, and emergency room visits) are estimated at 7%.

Estimated distribution of costs associated with illicit substance use. Québec, 2017

Data source: Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction and Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research (2017), Canadian Substance Use Costs and Harms Report.

11. What are the health care costs specifically associated with illicit substance use in Québec?

According to the most recent estimates (2017) from the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction and the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, the costs attributable to illicit substance use in Québec are $147.7 million. These are, however, partial costs, as they do not include the costs associated with emergency room visits, hospitalizations, and day surgeries (but do include specialized treatment, doctors’ compensation, and prescription medication). To compare, the estimated costs for all psychoactive substances combined is $2.2 billion. In total, all illicit substances combined represent 9% of these costs.

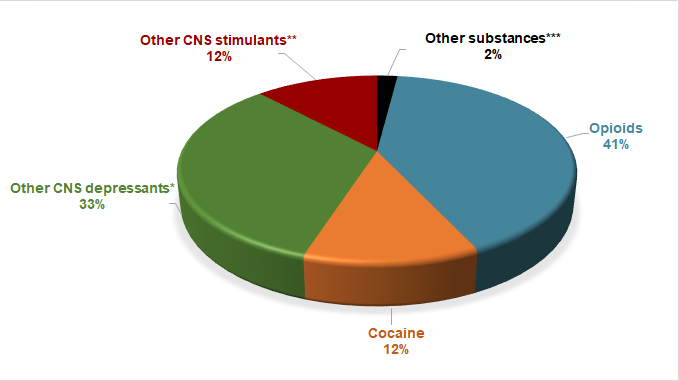

As demonstrated in the following figure, 41% of estimated health care costs related to illicit substances are attributable to opioid use. The remaining estimated health care costs attributable to illicit substance use are distributed among: other depressants (benzodiazepines, barbiturates, etc.), 33%; cocaine, 12%; other stimulants (amphetamines, methamphetamines, etc.), 12%; and other substances (hallucinogens, inhalants, etc.), 2%.

Estimated health care costs attributable to illicit substance use. Québec, 2017

*E.g., benzodiazepines, barbiturates, etc. Excludes opioids and alcohol.

**E.g., amphetamines, methamphetamines, etc. Excludes cocaine.

***E.g., hallucinogens, inhalants, etc.

Data source: Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction and Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research (2017), Canadian Substance Use Costs and Harms Report.

12. Do we know more about the illicit substances responsible for the highest criminal justice system costs in Québec?

Yes. However, the most recent estimates (2017) produced by the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction and the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research are fragmented and only include costs related to legal proceedings and correctional services (and therefore exclude costs related to police interventions).

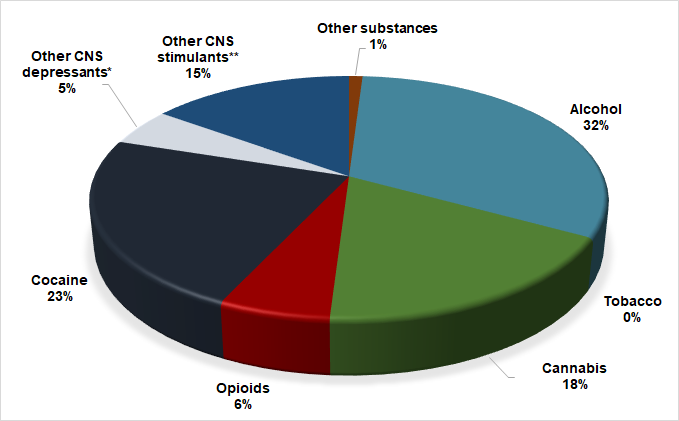

According to this source, for Québec in 2017, the costs related to illicit substance use (i.e., opioids, cocaine, depressants, stimulants, and “other substances”) are estimated at $985.7 million.

To provide a comparison, the estimated criminal justice system costs that year are $639.6 million for alcohol, $347.5 million for cannabis, and $1.2 million for tobacco.

In other words, according to these estimates, 50% of criminal justice costs are attributable to the use of illicit substances.

Estimated criminal justice costs associated with psychoactive substance use. Québec, 2017

*E.g., benzodiazepines, barbiturates, etc. Excludes opioids and alcohol.

**E.g., amphetamines, methamphetamines, etc. Excludes cocaine.

***E.g., hallucinogens, inhalants, etc.

Data source: Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction and Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research (2017), Canadian Substance Use Costs and Harms Report.

Drug Policy

13. What are the main reasons to remove criminal sanctions for simple possession of drugs?

There has been a general shift in the perspective surrounding drug policy. Problems surrounding illicit substances are now being approached as a public health issue rather than one of public safety or justice.

The fact that under the current prohibition framework, the offence of simple possession of drugs can lead to a criminal record, along with its consequences (e.g., difficulty finding a job or housing; prevention, in some cases, from travelling outside of Canada), is also among the most frequently cited reasons for adopting a new drug policy.

Due to stigma and various prejudices, many people who use drugs report that they limit their use of social services and health care for fear of being reported to law enforcement. Some people believe that changing the drug policy could reduce stigmatization and thus encourage people who use drugs to use the resources as needed. The inability to manage the overdose crisis is often considered a factor that justifies the need to modify the drug policy (also see questions 18 and 19).

Finally, it is known that the current drug policy incurs high financial costs (see the related section on the costs of psychoactive substances in Québec), while simple possession of drugs offences do not significantly harm public safety (in comparison, for example, with the harm that can be attributed to substance trafficking). It is therefore expected that reducing police interventions and legal proceedings will be economically beneficial.

14. Who are the actors in favour of adopting alternative approaches to illicit substances?

Drug user groups are, mostly, in favour of changing the drug policy.

Public health actors, along with numerous community actors and some researchers, are examining mechanisms and supplementary strategies to address some of the dangers associated with psychoactive substance use, including overdoses and death. Measures like “decriminalization” are often raised in this context by some of these actors. In regard to strategies, it should be noted that in 2021, British Columbia became the first Canadian province to submit an exemption request to Health Canada, pursuant to section 56 of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, that simple possession of drugs no longer be subject to criminal sanctions.

In February 2021, the federal Minister of Justice introduced Bill C-22. This bill chiefly aims to abolish the minimum prison sentences for simple possession of drugs. If it passes, individuals would only be arrested for simple possession if it constitutes a threat to public safety. They would be given the option to participate in a diversion program that provides access to health care and social services rather than face criminal charges.

In summer 2020, the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police, which represents 1,300 police forces, issued a statement in favour of changing the mode of regulation. The association agrees that the current approach is both costly and ineffective and that other mechanisms should be promoted, particularly with a view to referring individuals using these substances to treatment or other services tailored to their needs.

With regards to the federal government, the Minister of Justice issued new guidelines in 2020 to limit criminal prosecutions for simple possession of drugs to the most severe cases. These guidelines, however, do not apply in Québec, where the application of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA) is the responsibility of the Attorney General of Québec.

15. The current drug policy is considered one of “prohibition.” Can some of the existing measures and services offered in Québec help restrict the application of criminal law? And if so, how?

Some jurisdictions have more prohibitive policies than others

In Canada and Québec, and as has been demonstrated in a recent INSPQ report [available in French only], the current drug policy benefits from a range of harm reduction measures, including some that limit the criminalization of people who use drugs. For example, people are not subject to criminal sanctions when their consumption takes place at a safe consumption site or in an overdose prevention centre. Although the substances are illicit, police officers cannot intervene inside these sites or arrest anyone there in possession of these substances. Similarly, no one can be arrested simply for the possession of injection or inhalation equipment, even though the act of possessing them implies that they use illicit substances.

Furthermore, the Director of Criminal and Penal Prosecutions and the Minister of Justice of Québec have implemented some non-judicial programs and diversion programs [pages in French only] to which some individuals arrested for simple possession can be referred depending on their situation or the substance that led to their arrest. Under certain conditions (e.g., depending on the severity of the offense, the substance involved, and the quantity in possession), these programs offer alternative approaches to criminalization and can limit the criminal records received for simple possession.

16. Is changing the law absolutely necessarily from a public health perspective to better support people who use illicit substances?

Not necessarily.

A recent report from the INSPQ [available in French only] demonstrated that alternative approaches to criminalization that provide a health care or social services referral mechanism show promise, regardless of whether or not they are implemented following a change in legislation (see questions 20 to 24).

With regards to psychoactive substances, harm reduction is a public health objective. Another objective is to prevent substance use disorders or the deterioration of quality of life for people who use drugs. This means offering a timely range of services and care that responds to the various social and health care needs of people who use drugs. Notwithstanding, of the drug policy in place or whether or not there is a legislative change, these aspects are crucial from a public health perspective.

17. What can be done to reduce the harm associated with drug use without changing the law?

In Québec there are a range of measures (especially for harm reduction) and services to support people who use drugs. One of the challenges is to make them accessible throughout all regions of Québec in a timely manner. Moreover, better comprehension, especially among police officers, of the disorders related to substance use may also prove useful. This last aspect would also potentially reduce stigmatization and promote individuals’ use of health care and social services when they are required.

A recent report by the INSPQ [available in French only] highlighted the following supporting elements:

- The recognition of the diversity of needs of people who use drugs (including housing, mental health, social reintegration, etc.)

- The ease and rapidity of access to services

- The consistency between these services and the needs of people who use drugs

- The feeling, for people who use drugs, that they can access these services without being judged by care providers

- The involvement of people who use drugs in the implementation and provision of both services and care

- The acceptability of the existing measures to people who use drugs, police officers, actors, and the general population

Alternative approaches to criminalization and the overdose crisis

18. . In Québec and the rest of Canada, “decriminalization” and implementing alternative approaches to criminalization are often considered necessary to manage the overdose crisis involving opioids and other drugs. Is this realistic?

Because they obtain drugs illegally, some people who use opioids are likely to be subjected to police interventions. For fear of being reported to law enforcement, these individuals may avoid using health care and social services resources. Following this logic, decriminalizing simple possession of drugs—regardless of whether it involves a health care or social services referral mechanism—would remove the possibility of arrest leading to a criminal record, and therefore reduce stigmatization and encourage individuals to seek out the support they need.

In a recent report [available in French only], the INSPQ presents alternative approaches to criminalization that allow for police officers to connect people who use drugs to health care and social services. Overall, the results indicate that these measures show promise for acting on various determinants of health. Studies specifically measuring deaths and overdoses, although there have been few, have not shown any increase in deaths or overdoses after criminalization alternatives were implemented. If such measures were implemented in Québec, they would therefore likely contribute to managing the opioid overdose crisis.

19. What are other factors that explain the increase in opioid-related deaths and for which alternative approaches to criminalization are not a solution?

The increase in opioid-related deaths is a complex phenomenon that can be attributed to a multitude of factors that require actions on various levels. The aspects most commonly raised to explain the emergence of this crisis include:

- Opioid over-prescription, which leads to an increased risk of developing a use disorder if the treatment includes little or poor supervision

- Under-use of alternative treatments for non-cancerous pain relief

- Diversion of these substances

- The increased toxicity of illegally acquired opioids, which increases the risk of overdose and death for users

On another note, the increased risk of developing dependence following medical use suggests that opioid use disorders do not only affect those who are more likely to be criminalized, but also those who were prescribed these substances. It is difficult to establish how any form of decriminalization would have an impact on these people specifically. It appears, however, that some individuals would also benefit from support measures.

In summary, even though alternative approaches to criminalization could have positive effects and reduce opioid overdose deaths, it is important to keep in mind that overdoses (especially opioid-related) can be attributed to multiple causes. Accordingly, reducing overdose deaths entails a multitude of actions at different levels.

Some examples of alternative approaches

20. Portugal’s drug policy is often cited as an example of potential positive effects of “prohibition” alternatives. How would the Portuguese policy be described?

In 2001, Portugal became the first jurisdiction to decriminalize the use and possession of all drugs from a public health perspective. This process established a mechanism to divert drug offenders to health care and social services, namely the Commission for the Dissuasion of Drug Addiction (CDDA). Following a police arrest for simple possession of drugs, the professionals at these commissions, who come from the health care, public safety, and justice sectors, assess the individual to determine whether their drug use is problematic, at risk of becoming problematic, or occasional (and therefore not causing harm to their health or quality of life). Depending on the situation, they may act preventively, informing the person of the possible effects of their drug use. When necessary, they encourage the individual to obtain support, be it through treatment or other health care or social services. While this drug policy does not provide for criminal sanction, CDDA workers can impose administrative sanctions (fines, community service, prohibition from frequenting certain places or seeing certain people, etc.).

21. Has the Portuguese drug policy reduced the harm associated with drug use?

Not having a criminal record is a significant positive impact for people who use drugs. Moreover, the available data analyzed by the INSPQ [report in French] does not provide any evidence that the policy change led to harmful health effects for people who use drugs.

In regard to the objective of reducing high-risk drug use (that could lead to a use disorder) and use by injection, the available data suggest that Portugal has partially achieved their objective. Data also indicate that human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) cases in people who use injection drugs have decreased, more than in many European countries during the same period.

The data for the period preceding 2001 (decriminalization) are sparse. This limits the conclusions that can be drawn from the Portuguese approach and its effectiveness. Additionally, it is difficult to determine the extent to which the observed changes can be specifically attributed to this new drug policy and not the trends and movements (political, historical, etc.) observed in Portugal and its neighbouring countries concurrently.

The Portuguese experience demonstrated that it is possible to implement an alternative model to criminalization for drug use on a national scale while reducing certain negative consequences associated with a “prohibition” model. Its potential should not be overlooked as it demonstrates the possibility of implementing a concerted approach between actors from the healthcare network, social services, justice, and public safety.

22. Are there other countries that use similar approaches to those implemented by Portugal?

Yes. The INSPQ examined different alternative approaches to the criminalization of people who use drugs [document available in French only] from a public health perspective. All of the ten identified measures include targeted diversion to health and social services.

For example, the Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD) program was implemented in different American cities, and more recently some cities in the United Kingdom and South Africa.2 Like Portugal’s Commissions for the Dissuasion of Drug Addiction, this program is set up so that during a police stop, instead of making an arrest, the police officer can refer the individual to a healthcare professional to assess their needs and their drug use. Acting as a case manager, this professional then directs the person to the required services and care, regardless of whether they are directly related to drug use. For example, this can involve facilitating access to housing, mental health services, or employment reintegration. As for effectiveness, the program’s assessment indicates that it shows promise, especially for reducing problems related to health and various social costs (e.g., the costs of judicial processes, revenue losses, etc.). Unlike Portugal’s approach, the LEAD Program does not require any change to the law and is based on police discretion.

2Refer to: https://www.leadbureau.org/ and http://www.revolving-doors.org.uk/blog/police-led-diversion-%E2%80%93-l….

23. Could measures like the Commissions for the Dissuasion of Drug Addiction in Portugal and the LEAD program in the United States be implemented in Québec and achieve similar results?

These measures show promise. An assessment revealed positive impacts on the health of people who use drugs, which appears to be directly related to the implementation of these measures.

In sum, it is certainly possible that implementing such measures in Québec could have a beneficial impact on the overall health of people who use drugs. To increase their potential effectiveness, it is important that these measures adequately reflect the existing harm reduction and treatment services. For the best chance at success, existing services and resources should be adequate, accessible in a timely manner and tailored to the needs of people who use drugs, regardless of whether these needs are related to their drug use (e.g., mental health, low-threshold services, social reintegration, etc.). It would be advisable to offer support and ongoing training to public safety stakeholders to ensure they have a good understanding of these measures’ objectives and agree to play an active role.

Given the promising nature of these alternative approaches, it seems appropriate to consider their applicability in Québec while ensuring that they fall within the scope of a comprehensive and coherent strategy to promote health and prevent health problems associated with psychoactive substance use.

References

- Brisson, J. (2020). Les Commissions de dissuasion de la toxicomanie au Portugal : Mise à jour au regard de l’état de santé des personnes utilisatrices de drogues et de l’évolution de la consommation. Institut national de santé publique.

- Brisson, J., Blais, E., Gagnon, F., Lemay, S-A (2021). Les mesures alternatives à la criminalisation des personnes interpellées pour possession simple de drogues : une perspective de santé publique. Institut national de santé publique.

- Centre canadien sur les dépendances et l’usage de substances et Institut canadien de recherche sur l’usage de substances. Coûts et méfaits de l’usage de substances au Canada. En ligne : https://cemusc.ca/