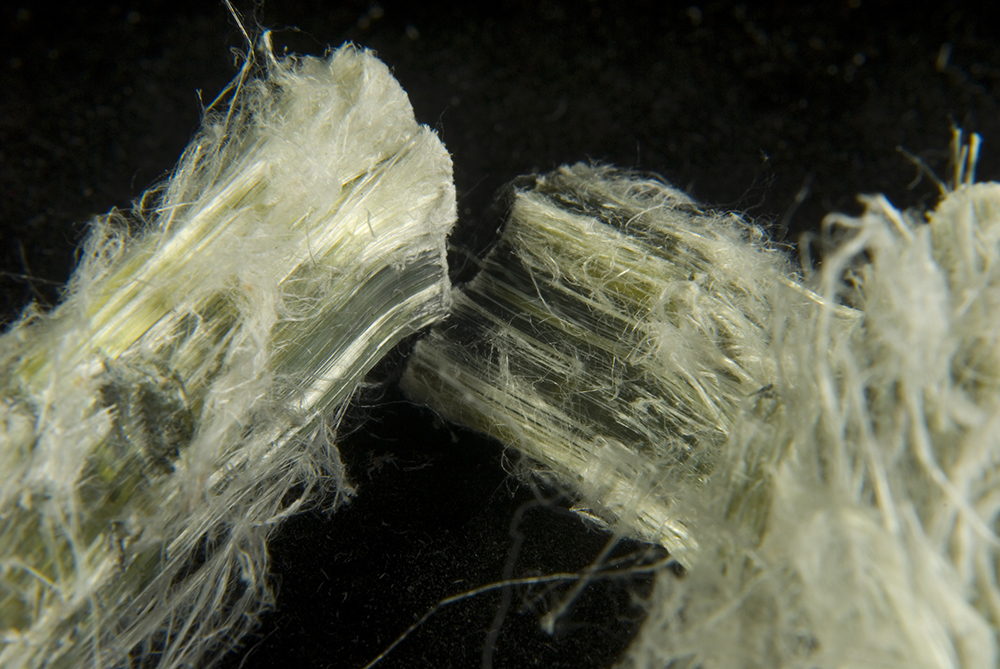

Asbestos

Since 2003, the Institut national de santé publique du Québec (INSPQ – Québec’s public health institute) has produced some fifteen publications describing asbestos exposure and asbestos-related diseases in Québec’s general population and its workers. The current state of knowledge leads to the conclusion that chrysotile asbestos is a human carcinogen and as a result, all the preventive and protective measures for the health of workers and the public must be enforced. However, the experience in Québec shows that there are serious difficulties in enforcing the recommended measures for the safe use of asbestos.

Additional information on Asbestos in Québec

Chrysotile: A proven human carcinogen

Several organizations, such as the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and the National Toxicology Program (NTP), concur that all types of asbestos cause several types of cancer (lung cancer, pleural mesothelioma and peritoneal mesothelioma) (INSPQ, 222). In 2009, the IARC added cancer of the larynx and of the ovary to this list, while at the same time upholding the links established for other diseases since 1978 (1). We are therefore faced with a substance that, in addition to causing chronic lung diseases, such as asbestosis, also causes cancers.

About the safe use of asbestos in Québec

The occupational exposure limit for chrysotile asbestos (1 fibre/ml) currently in force in Québec (2) is 100 times higher than the one prevailing in the Netherlands and in Switzerland (3) and it is ten times higher than the one adopted by many western countries and other Canadian provinces (4). Moreover, in the current state of knowledge, there is no cancer protective threshold for persons exposed to asbestos (5). The studies carried out in Québec in asbestos products factories and in the construction industry show that the current laws and regulations are not always enforced, thereby leading to the finding that asbestos is not used safely in these industries.

Read more

For example, in Montréal, at the end of the 1990s, 23 factories that manufactured asbestos products or used them in production were identified. Seven (30 %) of these factories showed problematic situations, with respect to standards being exceeded, despite the knowledge about the health risks, the regulations in force and the intervention of public health teams in these factories (INSPQ, 393). Ten years later, in 2008-2009, only nine factories were identified in Québec but in all of them, the employees were not working safely. Moreover, in one of these nine factories, significant exceedances of the exposure limit were observed, despite the use of prescribed work procedures (INSPQ, 1213).

The second important finding concerns the construction industry. In Québec, asbestos-containing materials were used abundantly in buildings constructed prior to the 1980s (5). However, in the past, no records were kept of the places where these materials were installed. Consequently, today, workers who repair older buildings do not protect themselves against this substance since they are not aware of its presence in their work environment. Furthermore, when employers and workers know that asbestos is present, it is difficult to enforce existing regulations because the protective measures are constraining. In 1998 the Commission de la santé et de la sécurité du travail du Québec (CSST – Québec workers’ compensation board) and public health authorities adopted a joint intervention program in the construction industry. Despite this, the number of non-compliance notices issued by CSST inspectors on these work sites have not decreased with the passing years, contrary to what should be observed (INSPQ, 1213). Consequently, considering first, that the results of the exposure measurements taken on Québec construction sites show exceedances of the exposure limit for chrysotile asbestos in 43 % of cases (INSPQ, 1213) and second, that the regulations are not always applied, it follows that workers are still at risk of developing asbestos-related diseases. These points lead us to conclude that in Québec, as in other western countries, the safe use of asbestos in construction seems to be impossible to achieve (INSPQ, 393).

Chrysotile and asbestos-related diseases

In a mortality study conducted in Québec, 38 mesothelioma deaths were observed up to 1992 among 10,918 asbestos mine and mill workers and workers in one asbestos products factory (8). A few years later, between 1988 and 2003, 59 pleural mesotheliomas were recognized as occupational pulmonary diseases in Québec’s asbestos mine and mill workers. Forty-three of these pleural mesothelioma cases died between 1993 and 2003 and were born after those who were included in the cohort of 10,918 workers, thereby doubling the number of mesotheliomas reported in this industry. Furthermore, between 1988 and 2003, 198 cases of asbestosis and 203 lung cancers were added to the mesothelioma cases already described (INSPQ, 1213). It is therefore difficult to dismiss the fact that in Québec, chrysotile asbestos causes asbestoses, lung cancers and pleural mesotheliomas.

Read more

Despite the large number of deaths observed in the mining sector, construction and maintenance workers currently generate the greatest number of cases at the CSST for one of these asbestos-related diseases (49.5 % of cases or 646 asbestoses, lung cancers and mesotheliomas) (INSPQ, 1213). Some sources suggest that the installation of amphibole asbestos explains this “rise” of diseases in construction and maintenance. Yet according to two studies carried out for the INSPQ, between 75 % and 95 % of the materials sampled on construction sites contained only chrysotile (INSPQ, 1213 and INSPQ, 986). It therefore becomes difficult to separate the role of one type of asbestos fibre from the role of another in the development of asbestos-related diseases, and even more difficult to outrightly deny the role of chrysotile by claiming that it was not used in buildings in the past.

References

- Straif K, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Baan R, Grosse Y, Secretan B, El Ghissassi F et al. A review of human carcinogens-part C: metals, arsenic, dusts, and fibres. Lancet Oncol 2009; 10(5): 453-4.

- Government of Québec. Regulation respecting occupational health and safety. R.S.Q., c. S-2.1, r. 19.01. 2009.

- www.dguv.de/ifa/en/gestis/limit_values/index.jsp (accessed October 10, 2012).

- www.carexcanada.ca/en/asbestos/ (accessed October 10, 2012).

- World Health Organization. Chrysotile Asbestos. Environmental Health Criteria 203; Geneva; 1998.